Zoe Carter paused at the heavy oak door of Professor Rosenberg’s study, the late-afternoon sun painting amber streaks across the worn stone floor. Beyond the mullioned windows, the Jerusalem hills rolled like ancient waves toward the horizon, olive groves glinting in the heat. Inside, floor-to-ceiling shelves bowed under leather-bound tomes—paleography manuals, genomic atlases, theological commentaries—each a testament to centuries of human inquiry. The polished oak desk at the room’s center was strewn with scroll photographs, ethics drafts, half-empty espresso cups, and an overturned quill; above, a brass chandelier whispered of old-world scholarship.

“Zoe,” Rosenberg began without looking up, fingers stained with ink. His silver hair was disheveled; dark circles traced eyes that had outlasted too many midnight sessions. He tapped a thick sheaf titled Consortium Principles. “We need to finalize this charter before the press release. Hesitate, and critics will pounce—they’ll claim we’re overstepping, and our funding could evaporate.”

She crossed the worn Persian rug, fingertips brushing the parchment. “Transparency and peer review,” she murmured, scanning bullet points. “Independent oversight. Chain-of-custody protocols. Representation from religious leaders, community stakeholders, and bioethicists.” She paused over a clause. “We should require dual-signatures on every data export—one from a scientist, one from a lay representative. Eliminate any single point of failure.”

Rosenberg leaned back, nodding. “And strict patent restrictions. All raw data in open-access archives within six months—no hidden repositories.”

Zoe jotted margin notes in precise strokes: timelines for preprint publication; tiers for embargoed findings; public dashboards for query tracking. “I’ll draft the outreach plan and legal summary. We must prove that science and scripture can coexist—neither undermines the other.”

He offered a tired smile. “Remember your first summer at Oxford—how awed you were by those medieval quad libraries?”

She tucked a loose strand of hair behind her ear. “I was eighteen, convinced tomes older than my country held life’s meaning.” She touched the framed photo of her UGA-at-Oxford cohort. “Let’s not repeat that naiveté.”

Seminar at the National Library

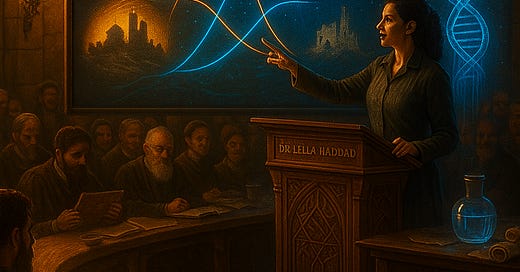

That evening, the vaulted lecture hall of the National Library thrummed with anticipation. Torch sconces cast warm pools of light on stone arches; rows of wooden benches creaked under a dozen assembled scholars, librarians, and journalists. Parchment-strewn tables formed a horseshoe at the front, bristling with tablets and notebooks. Rain pattered against high windows, lending the moment a hushed gravitas.

Dr. Leila Haddad—visiting from Oxford’s Faculty of Theology and Religion—stepped to the lectern carved with Hebrew and Arabic inscriptions. She paused, letting candlelight dance across her features, then began:

“In 1994, Doron Witztum, Eliyahu Rips, and Yoav Rosenberg first reported equidistant-letter sequences in Genesis (WRR1994). By 1997, Michael Drosnin’s The Bible Code popularized the idea (The Bible Code), and in 2006 it reached mainstream audiences via documentary. Critics like Brendan McKay’s team demonstrated comparable patterns in Moby-Dick (McKay et al.), showing statistical pliability.”

A soft murmur rippled through the audience as Haddad clicked to a slide of two curves: a sapphire line for random-text ELS rates, a crimson line for biblical-text rates.

“Our approach,” Haddad continued, “avoids these pitfalls. We map each Hebrew letter to its cognate amino acid, integrate 3D protein structures, and apply Bonferroni corrections to ensure true biological relevance.”

An archivist raised her hand. “How do you fend off confirmation-bias claims—that you see only the patterns you choose to see?”

Zoe stood, smoothing her blazer. “We predefine skip intervals—42 for thematic resonance, prime gaps for structural nuance—and cross-validate against independent genomic datasets,” she replied. “Our benchmark: correlation coefficients above 0.85 before we even consider publication. We don’t chase prophecy; we test sequence-structure hypotheses. We even integrate Orch OR quantum-coupling models (Orchestrated Objective Reduction), aligning Kabbalistic symbolism with peptide folding dynamics.”

Several in the audience nodded—some intrigued, some skeptical.

Haddad advanced to the next slide: a collage of authorship hypotheses, each illustrated with a symbolic icon:

Divine Authorship — God as the ultimate scribe

Proto-Civilizational Encoding — a lost advanced society from the Silurian age (Silurian hypothesis)

Extraterrestrial Intervention — the zoo hypothesis, aliens observing and seeding symbolic texts (Zoo hypothesis)

“If scripture is divine,” Haddad said, “we explore questions of transcendent intent. If it’s proto-civilizational, we seek archaeological echoes of cataclysmic erasures. If it’s extraterrestrial, we confront the notion of humanity as an interstellar experiment.”

A ripple of whispered excitement spread. Haddad let the weight of each possibility register.

“Our ELS pipeline tests for encoding strategies far beyond random noise—patterns that betray deliberate design, be it divine, human, or alien.”

A young scholar raised her hand. “Have you applied this to non-scriptural corpora under the alien model?”

Zoe: “Yes. We ran our codon-mapping ELS on scientific treatises, Victorian novels, even patent texts—alignment scores only spike when the text is intentionally designed, unlike natural literature.”

Haddad closed her laptop. “In summary, we proceed with three working hypotheses. Our next steps: expand to pre-exilic texts, non-Abrahamic scriptures, and oral traditions; refine quantum correlation thresholds in proteins like NRG1 and FOXP2; and seek convergence across theology, anthropology, and astrobiology.”

Rosenberg, leaning against the back wall, gave Zoe a supportive nod. She exhaled, adrenaline and excitement mingling—aware they’d set a new bar for interdisciplinary rigor.

Midnight Drafting and Morning Revelation

Back in Rosenberg’s study, they huddled over coffee-stained drafts. The final charter sections crystallized:

Public disclosure via bioRxiv preprints within 30 days of data release

Encrypted archival under nonprofit governance, per CIOMS guidelines

Annual ethical audits reviewed by interfaith councils

Community engagement through town halls and interactive webinars

Contingency plans for IP disputes—nonexclusive licensing, charitable-trust reserves

Over fresh espresso, Rosenberg insisted on “we suggest”—academic caution—while Zoe demanded “we shall”—binding clarity. They settled on “shall, unless superseded by external regulation.” He exhaled, then raised his cup: “That’s our ethical backbone.”

At dawn, Zoe powered up Rosenberg’s workstation and loaded the NRG1 3D structure in PyMOL. She overlaid 42-skip and prime-skip ELS hotspots as glowing spheres, residues corresponding to yod-heh-waw-heh (Y-H-W-H) in amber. Rotating the model, two spheres converged within the receptor-binding cleft—under six angstroms apart, ideal for hydrogen bonds and hypothesized quantum effects (Hameroff & Penrose, Orchestrated Objective Reduction).

Zoe (whispering): “It’s a living contact map—skip patterns encoding 3D interactions, not just linear text.”

Rosenberg peered over her shoulder. “Either ancient scribes anticipated folding kinetics…or someone handed them the blueprint.”

Zoe’s pulse thundered. She saved overlays to three air-gapped SSDs. “This bridges protein engineering and scriptural studies.”

The Breach

That evening, Zoe returned with fresh espresso to find the study in disarray: drawers yawned open, scroll photographs scattered, and her Faraday pouch lay sliced. The slot where her encrypted SSD had sat was empty.

Zoe (voice tight): “They breached our protocols—scripts, scans, backups: all gone.”

Rosenberg knelt among the wreckage, gathering scattered pages. “We need off-grid reconstruction. Now.”

Fingers trembling, Zoe dialed local security. The guard promised to check surveillance footage, but she felt exposed. “Mirna’s network won’t relent,” she muttered, recalling anonymous threats encrypted in her inbox.

Rosenberg rose, brushing dust from his lapel. “We’ll rebuild—smarter, stronger.”

Exodus to Oxford

By dawn she booked a red-eye to London, carry-on heavy with hastily copied scripts and Rosenberg’s shredded charter. On the flight she pinged Haddad via their post-quantum channel, summarizing the break-in and proposing “off-grid protocols.” Haddad’s reply arrived within the hour: blueprints for Oxford’s air-gapped lab, hardware-key rotation schedules, and plans for private night charters.

Three weeks later, Zoe slipped through wrought-iron gates behind St. John’s College, Oxford, where Haddad waited amid jasmine and orange blossoms. The air smelled of chalk and centuries.

Haddad (handing Zoe tea): “I’ve set up a secure lab at the Bodleian. Air-gapped servers, FIPS 140-3 hardware keys in sealed safes, two-factor biometric locks, and a Faraday vault for uplinks.”

She slid a new SSD across the stone table—preloaded with backup scripts, ELS variants, and the updated letter→amino-acid mapping from our GitHub repo.

Zoe held the drive like a relic. “Thank you. But if they can breach Jerusalem…will they follow us here?”

Haddad’s eyes hardened. “We’ll work under aliases, decoy convoys, and private flights. Oxford’s stones are thick, but our secrecy must be thicker.”

Reflection and Resolve

That evening, Zoe retreated to a rooftop terrace overlooking Oxford’s dreaming spires. The Sheldonian Theatre glowed beneath a starlit sky; distant string quartets drifted through open windows. She opened her leather-bound notebook and wrote:

Our burden: marry faith, science, and quantum insight with integrity.

Guard the code as a gift, not a weapon.

Publish truth; protect discovery.

Her mind drifted to that first summer at Oxford—wandering Oriel College’s cloisters, awed by tomes older than nations—and to Jerusalem’s adhan echoing against ancient domes. In memory, they merged into a single harmony of belief.

Zoe closed the notebook and gazed at the moonlit sky. The weight of centuries pressed on her shoulders, but so did their promise: that knowledge, shared wisely, could illuminate humanity’s path. With Rosenberg’s trust and Haddad’s fortress behind her, she felt the Scholar’s Burden settle firmly—but not unbearably—upon her. She was ready.